-

One Work One Story : Portrait de Meijer de Haan

-

-

Meijer de Haan and Gauguin, background and Breton interlude

De Haan, a painter of some success with Jewish genre works had had a tumultuous period, brought about by the unfavourable reception of the work that he had considered would be his masterpiece, Uriel Acosta. His credibility as an artist under fire, he cut ties (albeit with an allowance provided by his family) and moved to Paris. Here he lodged with fellow Dutchman Theo van Gogh in the room vacated by his brother Vincent, with whom he had corresponded. Walking in these footsteps he hoped to learn how to be more ‘Impressionist’ in his style and sought a tutor. Gauguin was often a guest of Theo’s and upon Theo’s engagement to be married in early 1889, De Haan moved to Brittany, where Gauguin visited every year and had suggested to sample Pont Aven by way of inspiration.In August of that year the pair stayed together in Le Pouldu, with De Haan paying for Gauguin’s board and lodging in exchange for being his teacher. By October the pupil had proven himself well enough to take on a joint project: the decoration of the dining are of the inn where they were staying. The work they produced was covered over in the 1920s, but later uncovered, restored and sold. -

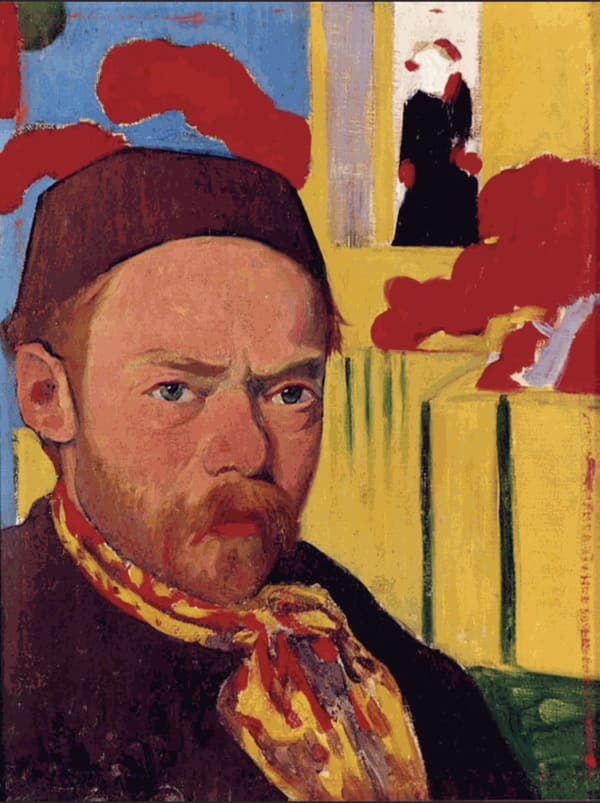

In these two bold self portraits by De Haan we can see him fully embracing the new styles and techniques from his 'teacher.' He incorporates ideas of Japonism, even making a feature of this in the portait on the left. He may have seen Japanese prints in the Van Gogh's collection and been aware of the influence on Vincent's work. Using the synthetist style Gauguin developed in Pont Aven, De Haan styles himself as a Breton in the portrait on the right, literally embodying this new style.

-

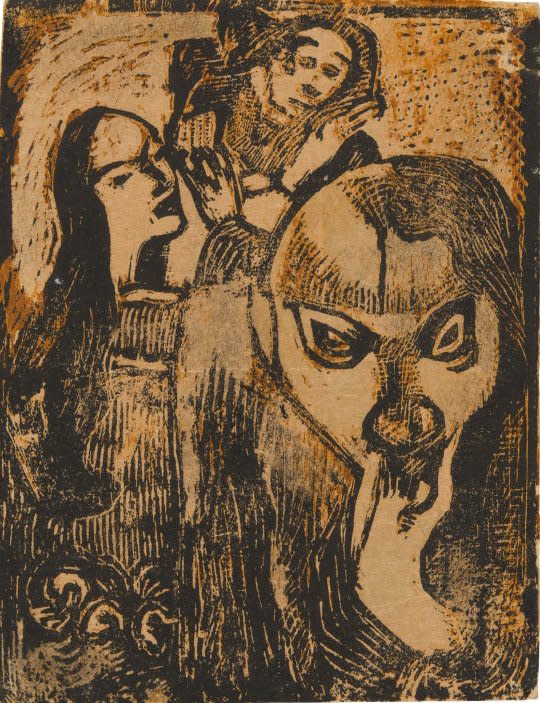

Paul Gauguin

Portrait de Meijer De Haan ou Mélancolie, c.1889Ink and pencil on paper

29.8 x 19.1 cm

11.7 x 7.5 inches -

De Haan as the subject

In this drawing we see de Haan huddled over a book, his awkward position partly due to his hunched back (most probably caused by a Tuberculosis of the bones affecting him since childhood) which lends the drawing continuous contours, the eye being drawn in a circle around his shoulder, down and around up his arm to his bearded face, held in his oversized hand. His proper right eye bulging intently downwards, we are drawn to see a notebook he is studying. The viewer wonders what the subject is so intently reading? It has been suggested it was a sketch book as Gauguin pasted his drawings into books of this size. The pupil avidly studying the works of his master? In the painted works the sketchbook is replaced by two books: Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle and Paradis Perdu (Paradise Lost) by John Milton. These titles are not arbitrary but rather can be perceived as a nod to his friend's state of mind: the idealism of the shedding of old ideas and finding new doctrines that befit the times and of the renunciation of his Jewish Faith.

-

Portrait of Meijer de Haan, 1889, Paul Gauguin,

Watercolour and pencil on paper, 16.4 x 11.1cm

Courtesy The Museum of Modern Art, New York -

A Transitional time

This study is an important part of this series of works made at this juncture of Gauguin’s life and the episode and works he made during his stay at Le Pouldu with De Haan would have a lasting influence on his future work. De Haan was in fact set to travel with him to Tahiti in 1891, but ill health prevented him.On April 4th 1891, Gauguin set sail for Tahiti from Marseille. In Tahiti, the artist continued his research on colours, developing a harmonisation of colours that completed the signification of symbols in paintings. The tones merged or opposed themselves in rhythm, leading to a symphonic of various elements. In this context of exploration his works on paper became rarer, the artist favouring the immediacy of painting and its symbolic strength.However, The Le Pouldu story continued. It was to become an ongoing saga for Gauguin on his return from Tahiti, and he became embroiled in a legal battle in 1894 to recover the artworks he had been obliged to leave with Marie Henry (owing her rent). Whilst there, he was assaulted one evening whilst out with friends and was left unable to paint for some months. In defeat, having lost the case, unable to retrieve his works which included many paintings and drawings, he could only think about returning to his Nirvana. -

A continuing legacy for Gauguin

Despite the unfortunate end to his Le Pouldu experience and the death of Meijer de Haan in 1895, the studies and ideas produced by the work which Gauguin executed during his time there were an important stepping stone to the work produced in Tahiti.

Once in Tahiti Gauguin would remember his friend and continued to use him as a motif in his works. We can recognise him in the two works here, using the same positioning of the head as in the study, looking down pensively, his chin leaning on his hand, partially covering his mouth. The large blue almond-shaped eyes and of course shock of red hair. Here however, the image of De Haan goes beyond the personal, beyond even caricatural representation, becoming more symbolic. He continues to appear in various works, right up to Gauguin's last series of works in the Marquesas Islands.